"'Listen.' Harold fell into the agitated intensity of a scientist impatient with methodology. 'Can we try something here?'

'Of course. Name it.'

He looked sidelong at me. Not wanting to overstep. 'Kahneman and Tversky?'

I smiled. Funny: Harold would not be impressed with my matching the obscure tags, recent additions to my own neural library. He took that much for granted. Just your garden-variety marvel.

I improvised for Helen a personal variation on the now-classic test. 'Jan is thirty-two years old. She is well educated and holds two advanced degrees. She is single, is strong-minded, and speaks her piece. In college, she worked actively for civil rights. Which of these two statements is more likely? One: Jan is a librarian. Two: Jan is a librarian and a feminist.'

'It knows the word "feminist"?' Mina lit up, arcing into existence at the idea.

'I think so. She's also very good at extending through context.'

Once more, Helen answered with a speed that winded me, given the pattern-sorting she needed to reach home. 'One: Jan is a librarian.'

Harold and I exchanged looks. Meaning?

'Why is that more likely, Helen?'

'Helen? It has a name?'

'That is more likely because one Jan is more likely than two.'

Now Harold took a turn laughing like an idiot.

'Wait a minute,' Mina said. 'I don't get it. What's the right answer?'

'What do you mean, what's the right answer?' Harold, raging affronted fatherdom. 'Think about it for ten seconds.'

'Well, she has all these feminist things about her. So isn't it more likely that she would be a feminist librarian than just a ...?'

Mina, seeing herself about to label the part more likely than its whole, threw her hand over her mouth and reddened.

'I can't believe it. I've worked my mental fingers to the bone for you, daughter.'

Harold's growl was motley at best. Helen, choosing the right answer for the wrong reasons, condemned herself to another lifetime of machinehood. Harold's girl, in picking wrongly for the right reasons, leaped uniquely human.

He cuffed her mussed hair, the bear teaching the cub to scuffle. 'I'm deeply disappointed in you.'" -- Richard Powers (1995). Galatea 2.2, Farrar Straus Giroux (p. 221)

Friday, December 29, 2006

Behavioral Economics In A Novel

Thursday, December 28, 2006

Why No More Great "Libertarian" Economists?

"...What distinguishes the new generation [e.g., Joe Stiglitz, Paul Krugman, and Richard Freeman] of policy-relevant mainstream economists? They are not, alas, philosophical Keynesians. But they often arrive at Keynesian policies by elaborate neoclassical routes - by building asymmetric information or increasing returns or externalities into an otherwise orthodox model and tracing through the implications. They combine a facility with this method and an openness to empirical observation, the choice of important cases, and a willingness to tackle hard problems of policy design and to consider ingenious solutions to particular policy problems. Moreover, they are willing to devote time and energy to explaining the issues to a larger public - whether in economic policy journals like Challenge or broader public forums like The New York Times. In these respects they do resemble Keynes, who remains the ultimate example of a modern economist who could do it all.Galbraith's paper is part of a symposium. The symposium is organized around comments on a paper by Daniel B. Klein. Gordon Tullock, Deidre McCloskey, Israel Kirzner, Charles Goodhart, Robert Frank, and James Galbraith provide the comments.

So what is the problem over there on the libertarian side? Klein is right: there is a problem - the libertarians are strangely quiet these days. One might think that new libertarian voices would emerge in the Bush era, when many actual libertarians are closer to state power than ever before. But no. There are no new Friedmans, no Hayeks, no Wanniskis, no Gilders to chorus in the new regime, to lend it an air (badly needed one might add) of intellectual authority.

I think I know the reason. The libertarians, let me suggest, have lost the courage of their convictions. Libertarian followers of Lucas, unlike, say, those of Tullock, rarely speak on public questions for a simple and well-considered reason. What they do is, indeed, very implausible. It cannot be conveyed to the ordinary literate and sensible person because, once the assumptions are spelled out, the ordinary literate and sensible person will reject them.

Furthermore, no one any longer believes Milton Friedman's old methodological saw about false assumptions being irrelevant - so long as the 'implications' are valid. The point made against Friedman long ago by Tjalling Koopmans - that this allows one to escape difficulties by reclassifying unpersuasive implications as assumptions - is elementary enough to be grasped intuitively by those who will never read Koopmans. Better to be a scholastic, in short, than a figure of fun.

A second group of scholastics is silent on policy questions for a different reason: the scholasticism that is increasingly up-and-coming inside economics no longer supports the libertarian view. It would be quite dangerous for a serious student of, say, game theory or non-linear dynamics or of models with multiple equilibria to delve too deeply into the policy implications of such work. Such forms of modern economics simply no longer support the libertarian political viewpoint, and to make this too widely known would greatly jeopardize right-wing support for mainstream economic research..." -- James K. Galbraith (2001). "Response from an Economist who also Favors Liberty", Eastern Economic Journal, V. 27, Iss. 2: 227-299.

Tuesday, December 26, 2006

Robbins Mistaken, Morgenstern Insightful

Mention of "Economics 101" or principles of economics seems to often call forth divergent attitudes, as in the comments to this Crooked Timber post. These attitudes go back at least fifty years.

(Aside: I appreciate comments. I realize I am as slow in forming my thoughts into intelligible responses, including the acknowledgement of valid points, as DSquared is in posting promised book reviews.)

"The efforts of economists during the last hundred and fifty years have resulted in the establishment of a body of generalisations whose substantial accuracy and importance are open to question only by the ignorant or the perverse." - Lionel Robbins (1945). An Essay on the Nature & Significance of Economic Science, Second Edition, Revised, Macmillan and Co.Contrast Oskar Morgenstern (1941, "Professor Hicks on Value and Capital", Journal of Political Economy, V. 49, N. 3 (June): 361-393). Morgenstern notes that Hicks claims to have a new theory. This theory became the foundation for introductory or intermediate economics. Yet, as Morgenstern notes, Hicks ends up with the same conclusions. Morgenstern doubts that Hicks' work can stand up to a rigorous critique.

(Aside: I appreciate comments. I realize I am as slow in forming my thoughts into intelligible responses, including the acknowledgement of valid points, as DSquared is in posting promised book reviews.)

Friday, December 22, 2006

Conservative Paul Krugman

"In a saner political environment, the economic logic behind Rubinomics would have been compelling. Basic fiscal principles tell us that the government should run budget deficits only when it faces unusually high expenses, mainly during wartime. In other periods it should try to run a surplus, paying down its debt." -- Paul Krugman, "Democrats and the Deficit", New York Times, 22 December 2006I thought principles tell us that we should use government to develop institutions (e.g., unemployment insurance) that provide automatic fiscal counter-cyclical stimulus.

Furthermore, I don't know why I should believe the economy is supply constrained in the long run.

Update: Added a couple more links. One, by exhibiting a different rightist brand, only reinforces my opinion that Krugman is an example of an intelligent conservative.

On "Marxism and the Left"

I tried to leave this as a comment on a Michael Greinecker post. But something must have gone wrong between the seat of my chair and my keyboard.

I was not inclined to argue about the first sentence, "I will not go into arguing what 'real' Marxism is or how well it is founded in the writings of Marx." Then I clicked on the links and saw they were all Analytical Marxists.

Anyways, why is the word "implicit" in the phrase "Concerning the implicit value judgements in Marxism"? Is it so that one can assert exploitation is a normative concept, despite explicit statements by Marxists and scholars of Marx otherwise? I don't disagree that an argument can be developed here.

I would think Marxist political parties around the world have by now developed views on ecology; on discrimination based on ethnic, gender, gender preferences, etc.; and on access issues. I assume the objection is whether such concerns can be coherently integrated into the theory Marxists use.

By the way, my reaction to Mankiw's comment on the core was also to think of John Roemer.

(You might want to fix the spelling of the post title.)

I was not inclined to argue about the first sentence, "I will not go into arguing what 'real' Marxism is or how well it is founded in the writings of Marx." Then I clicked on the links and saw they were all Analytical Marxists.

Anyways, why is the word "implicit" in the phrase "Concerning the implicit value judgements in Marxism"? Is it so that one can assert exploitation is a normative concept, despite explicit statements by Marxists and scholars of Marx otherwise? I don't disagree that an argument can be developed here.

I would think Marxist political parties around the world have by now developed views on ecology; on discrimination based on ethnic, gender, gender preferences, etc.; and on access issues. I assume the objection is whether such concerns can be coherently integrated into the theory Marxists use.

By the way, my reaction to Mankiw's comment on the core was also to think of John Roemer.

(You might want to fix the spelling of the post title.)

Tuesday, December 19, 2006

Heresy From J. A. Hobson

"Among the business and professional classes and their economic supporters the conviction holds that any property or income legally acquired represents the productive services rendered by its recipient, either in the way of skilled brain or hand work, thrift, risks, or enterprise, or as inheritance from one who has thus earned it. The notion that any such property or income can contain any payment which is excessive, or the product of superior bargaining power, never enters their minds. Writers to The Times, protesting against a rise in the Income Tax always speak of their 'right' to the income they have 'made', and regard any tax as a grudging concession to the needs of an outsider, the State.

So long as this belief prevails all serious attempts by a democracy to set the production and distribution of income upon an equitable footing will continue to be met by the organized resistance of the owning classes, which, if they lose control of the political machinery, will not hesitate to turn to other methods of protecting their 'rights'." -- J. A. Hobson, Confessions of an Economic Heretic, as quoted in C. E. Ayres's The Divine Right of Capital (Houghton Mifflin, 1946)

Income Inequality in the U.S.A.

I don't know Alan Reynolds. Apparently he writes for the funny pages of the Wall Street Journal. Thus, I assume, he must be a serial prevaricator. Anyway, apparently the other day he wrote:

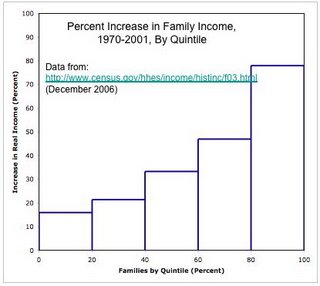

A fundamental contrast in the Post (World) War (II) period in the United States is that between the staircase and the picket fence. During the Golden Age, income increased about the same rate for all quintiles. That is the picket fence. About 1970, maybe with the end of the Bretton Woods system, something changed. Then one sees the staircase pattern, shown below. As I understand it, this pattern holds across a wide variety of time series (e.g., individuals or families) on various types of data (e.g., income, wealth, or wages). Details differ, of course, depending on exact time periods or time series used. For example, the first step falls, instead of rising a small amount, only in some periods for some measures. (And income mobility did not improve during the staircase years, either.)

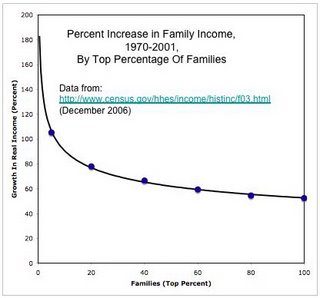

I could look for many references, other than Piketty and Saez, that draw the same basic picture. But I think I'll construct the staircase myself with some data from the U.S. Census Bureau. Figure 1 shows the staircase. Figure 2 shows the same data, analyzed a different way. It also shows a log-linear regression line, from which one can extrapolate how much the income of the top 1%, for example, has increased over the same period. If one wanted, one could fit a regression with each year. This would estimate a time series over the period.

"The incessantly repeated claim that income inequality has widened dramatically over the past 20 years is founded entirely on [Piketty and Saez's] seriously flawed and greatly misunderstood estimates of the top 1% alleged share of something or other"I don't know what "20 years" has to do with anything. And Piketty and Saez's novel contribution was not the documentation of increased inequality.

A fundamental contrast in the Post (World) War (II) period in the United States is that between the staircase and the picket fence. During the Golden Age, income increased about the same rate for all quintiles. That is the picket fence. About 1970, maybe with the end of the Bretton Woods system, something changed. Then one sees the staircase pattern, shown below. As I understand it, this pattern holds across a wide variety of time series (e.g., individuals or families) on various types of data (e.g., income, wealth, or wages). Details differ, of course, depending on exact time periods or time series used. For example, the first step falls, instead of rising a small amount, only in some periods for some measures. (And income mobility did not improve during the staircase years, either.)

I could look for many references, other than Piketty and Saez, that draw the same basic picture. But I think I'll construct the staircase myself with some data from the U.S. Census Bureau. Figure 1 shows the staircase. Figure 2 shows the same data, analyzed a different way. It also shows a log-linear regression line, from which one can extrapolate how much the income of the top 1%, for example, has increased over the same period. If one wanted, one could fit a regression with each year. This would estimate a time series over the period.

|

| Figure 1: Increase in Inequality Over 30 Year Span |

|

| Figure 2: Increase in Income In Top Percentiles |

Monday, December 18, 2006

A Post Keynesian Blog

After exploring his site, I find I should recognize Thomas Palley's work. I may have even read one or another of his papers, since the Cambridge Journal of Economics and the Journal of Post Keynesian Economics are two journals I try to read fairly regularly. Certainly some of the views Palley expresses on his blog, such as about the role of power and institutions in income distribution, seem to me to reflect a Post Keynesian perspective on economics. I am adding Palley to my weblog.

Saturday, December 16, 2006

Bah, Humbug

1.0 Introduction

This post presents an argument I get from Shaikh (1974). During the post (World) War (II) "golden age", the share of profits in U.S. national income stayed fairly constant. As a matter of algebra, an aggregate Cobb-Douglas production function fits the data. One cannot legitimately cite the goodness of such a fit as empirical evidence for the aggregate marginal productivity theory of distribution. The theory has not passed any potentially falsifying empirical test.

Shaikh built on past work in developing his argument, and a body of more recent work has extended and generalized the argument. Why do economists continue to use measures of Total Factor Productivity and Solovian growth theory when they have neither theoretical nor empirical support?

2.0 A Common Version Of Aggregate Neoclassical Theory

Consider the Cobb-Douglas production function:

Now impose further neoclassical assumptions. By the exploded aggregate neoclassical theory, competitive firms are maximizing profits when the interest rate is equal to the marginal product of capital:

3.0 Some Accounting Identitites

Begin anew. I start with the accounting identity that national income is the sum of total wages and total profits:

Take integrals of both sides:

Update: Originally posted on 5 August 2006. Updated to provide better formatted equations.

Reference

This post presents an argument I get from Shaikh (1974). During the post (World) War (II) "golden age", the share of profits in U.S. national income stayed fairly constant. As a matter of algebra, an aggregate Cobb-Douglas production function fits the data. One cannot legitimately cite the goodness of such a fit as empirical evidence for the aggregate marginal productivity theory of distribution. The theory has not passed any potentially falsifying empirical test.

Shaikh built on past work in developing his argument, and a body of more recent work has extended and generalized the argument. Why do economists continue to use measures of Total Factor Productivity and Solovian growth theory when they have neither theoretical nor empirical support?

2.0 A Common Version Of Aggregate Neoclassical Theory

Consider the Cobb-Douglas production function:

where Y(t) is national income at the indicated time, K(t) is the value of the capital stock, L(t) is labor services, A(t) represents technical progress, and(1)

The Cobb-Douglas production function can be written in a per-worker form:(2)

That is, Equation 1 is equivalent to Equation 4:(3)

where y(t) is national income per worker and k(t) is the value of the capital stock per worker. Take natural logarithms of both sides:(4)

I derive below the Cobb-Douglas production function, in the form of Equation 5, from the assumption that the profit share is constant, independently of whether competitive profit-maximizing firms follow marginal productivity theory or not. This derivation is also independent of whether or not production functions can be aggregated, either across firms or across industries.(5)

Now impose further neoclassical assumptions. By the exploded aggregate neoclassical theory, competitive firms are maximizing profits when the interest rate is equal to the marginal product of capital:

where r(t) is the interest rate. That is, according to neoclassical theory, if the economy’s technology can be represented by an aggregate Cobb-Douglas production function and competitive firms maximize profits, then the share of profits in national income is constant:(6)

where P(t) is total (accounting) profits.(7)

3.0 Some Accounting Identitites

Begin anew. I start with the accounting identity that national income is the sum of total wages and total profits:

where W(t) is total wages and w(t) is the wage. It is convenient here to do the algebra with quantities expressed per worker:(8)

Below, I need the wage share in national income expressed as the difference between unity and the profit share:(9)

Differentiate Equation 9 with respect to time to obtain Equation 11:(10)

One performs some apparently unmotivated alebraic manipulations on Equation 11 to obtain Equation 12:(11)

It is worth emphasizing that, so far in this section, all I have been doing is manipulating accounting identities. No additional theoretical or empirical structure has been imposed. I now assume that the profit share is constant, by whatever mechanism brings this constancy about. Equation 12 becomes Equation 13:(12)

Equation 13 expresses a growth-accounting relationship. The left hand side is the rate of growth of national income. The quantities in square brackets on the right hand side are the rate of growth of the wage, the rate of growth of capital per worker, and the rate of growth of the interest rate, respectively.(13)

Take integrals of both sides:

Equation 14 is a Cobb-Douglas production function, in the form of Equation 5, where technical progress is:(14)

So much for Solow's "Nobel" prize.(15)

Update: Originally posted on 5 August 2006. Updated to provide better formatted equations.

Reference

- Shaikh, Anwar (1974). "The Laws of Production and Laws of Algebra: The Humbug Production Function", The Review of Economics and Statistics, V. 56, Iss. 1 (Feb.): pp. 115-120

Thursday, December 14, 2006

Silliness From Edward Prescott

Some bloggers have recently commented on an editorial in the funny pages of the Wall Street Journal. This is the same Edward Prescott, who, after co-winning the "Nobel" prize in economics in 2004, was interviewed by the Arizona Republic. And Prescott said then, "It's easy to get over $200,000 in income with two wage earners in a household."

The engineers I know, when designing filters and otherwise applying the theory of linear systems, have some reason to believe that sytems they are modeling are linear. I don't see the same practical concern in economics. Here's an article that I like on mistaken consensus beliefs among mainstream macroeconomists:

The engineers I know, when designing filters and otherwise applying the theory of linear systems, have some reason to believe that sytems they are modeling are linear. I don't see the same practical concern in economics. Here's an article that I like on mistaken consensus beliefs among mainstream macroeconomists:

- White, Graham (2004). "Capital, Distribution and Macroeconomics: 'Core' Beliefs and Theoretical Foundations", Cambridge Journal of Economics, V. 28: 527-547

A Plea for a Pluralistic and Rigorous Economics

Thomas Palley makes some assertions about "The Knowledge Police in Economics" (via Mark Thoma). One of the commentators on Mark Thoma's post points out some brouhaha over the American Economic Association (AEA) policy on common affirmative action language in job ads.

When encountering such contretemps, I try to recall that they are not unique in the recent history of the AEA. In this post, I recall some AEA committees I think relevant to the discussion. The Committee on the Status of Women in the Economics Profession (CSWEP) had an important role in the founding of the International Asociation for Feminist Economics (IAFFE). (I read Amartya Sen - who was a student of Joan Robinson - as supporting feminist economics.)

I recall reading the report of the AEA Commission on Graduate Education in Economics (COGEE). I guess this report is:

A later AEA committee, headed by Thomas Schelling, looked into the openness of the AEA journals. I guess I want to read this:

When encountering such contretemps, I try to recall that they are not unique in the recent history of the AEA. In this post, I recall some AEA committees I think relevant to the discussion. The Committee on the Status of Women in the Economics Profession (CSWEP) had an important role in the founding of the International Asociation for Feminist Economics (IAFFE). (I read Amartya Sen - who was a student of Joan Robinson - as supporting feminist economics.)

I recall reading the report of the AEA Commission on Graduate Education in Economics (COGEE). I guess this report is:

- Krueger et al. (1991). "Report of the Commission on Graduate Education in Economics", Journal of Economic Literature, V. 29, N. 3: 1035-1053

A later AEA committee, headed by Thomas Schelling, looked into the openness of the AEA journals. I guess I want to read this:

- Schelling, Thomas (2000). "Report on the AEA Committee on Journals", American Economic Review, V. 90, N. 2: 528-531.

Tuesday, December 12, 2006

Krugman Gathers No Moss

In a recent article I otherwise like, Paul Krugman [1] writes:

I found out about this article from this bit of silliness:

[1] I'm generally not all that happy with Krugman as an economist.

"...last fall ...the House and Senate passed rival tax-cutting bills... The Senate bill was devoted to providing relief to middle-class wage earners: According to the Tax Policy Center, two-thirds of the Senate tax cut would have gone to people with incomes of between $100,000 and $500,000 a year. Those making more than $1 million a year would have received only eight percent of the cut." -- Paul KrugmanI think this can give the misleading impression that income between $100K and $500K is "middle income". I know that elsewhere in the article Krugman gives figures that show otherwise.

I found out about this article from this bit of silliness:

"Still recovering from the mild case of indigestion I developed after reading Paul Krugman's ignorant, communistic screed in the latest issue of Rolling Stone magazine..." -- Taylor

[1] I'm generally not all that happy with Krugman as an economist.

Hahn and Harcourt Amusing the Crowds

"During my time at Cambridge in the 1980s and 1990s I had a number of public debates with Frank Hahn, usually before the undergraduate Marshall Society, over the issues associated with different approaches to economics. The first was in the early 1980s and the room, a large one, was packed out. I as perceived to have had the better of the exchanges (there was a large Italian contingent present!). By the last exchange, though, the numbers had fallen considerably. Moreover, our arguments had not changed that much, but there was now much sympathy among the students for Hahn's views. I often clashed with Hahn in the Faculty coffee room. He has the makings of a splendid intellectual bully and he was always surrounded by acolytes, to which admiring crowd he could play shamelessly. Once he portrayed me falsely as a neo-Ricardian (I was actually attacking the way Hahn was caricaturing Pierangelo Garegnani's views, not defending the views as such) and he was delighted when in the end I lost my cool and became heated in my replies (when I could get a word in edgeways). He said something to the effect: 'Look at his red face and hear his incoherent utterings, he is mad like all neo-Ricardians'. As at much the same time Terry O'Shaughnessy and I were having vigorous debates with John Eatwell and Murray Milgate concerning the neo-Ricardian long-period interpretation of Keynes, this was a bit rich." -- G. C. Harcourt, "40 Years Teaching Post Keynesian Themes in Adeliade and Cambridge"

Sunday, December 10, 2006

Literature On Sen's Capabilities-Based Approach?

Can anybody recommend to me introductory literature on Amartya Sen's capabilities-based approach to economic welfare? Sen seems to have written a lot. Where should one start?

I need literature that suggests how to encapsulate aspects of Sen's theory in equations. Ultimately, I am interested in including a function in simulations, including asessing the effect of a well or ill fed population.

I need literature that suggests how to encapsulate aspects of Sen's theory in equations. Ultimately, I am interested in including a function in simulations, including asessing the effect of a well or ill fed population.

Saturday, December 09, 2006

Evan Jones on Galbraith Obits

According to Evan Jones, some obituaries of John Kenneth Galbraith

Presumably, my Galbraith obit is not included in Jones' critique.

"tell us more about the economics profession than they do about Galbraith. They provide an indirect vehicle for understanding the peculiar character of that profession. The criticisms expose what is acceptable ‘conventional wisdom’ as Galbraith himself would have called it. The reader can also discern in these criticisms dishonesty and incoherence...

...Galbraith's lesson in death is that the successful reproduction of the capitalist socio-economic system requires the perennial obfuscation of how it works."

Presumably, my Galbraith obit is not included in Jones' critique.

Wages And Employment Not Determined By Supply And Demand

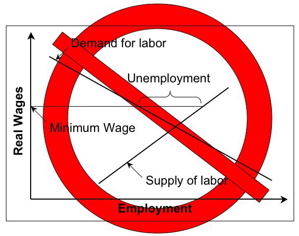

You will often find people fooled by incorrect teaching of introductory microeconomics into believing that minimum wages are a hindrance to increased employment.

The invalid argument behind this position is shown in a simple diagram of the labor market. The x axis is the level of employment. (In other words, the x axis is the flow of labor services.) The y axis is the wage, that is, the price of labor services. We are only interested in the region where both employment and the wage are positive. The supply of labor is typically drawn as an upward-sloping line, showing more people want jobs at a higher wage. The demand for labor from firms is a downward-sloping line. The point of interestion shows the market-clearing wage (on the y axis) and the level of employment when the market clears. A law imposing a minimum wage is represented by a horizontal line above the level of the market-clearing wage. Since labor demand slopes down, this line intersects the demand curve at a level of employment less than the market-clearing level. Furthermore, the horizontal distance along this line between this point of intersection and the point of intersection of this horizontal line with the supply curve shows the level of unemployment ultimately created by the imposition of a minimum wage.

But it has been known for at least a third of a century that wages and employment cannot be explained in competitive labor markets by the interaction of well-behaved supply and demand curves.

Consider firms in a vertially integrated industry producing some quantity of net output. The firms know of various processes for producing commodities in each sector of the industry. Given prices, including wages, they choose the cost-minimizing technique. In a situation of capital-reversing (also known as a positive real Wicksell effect) firms adopt a technique which employs more labor per unit output at a higher wage.

Now this adoption of a more labor-intensive technique might be swamped by the effect on the level of output. But, as far as I know, nobody thinks that the income effect of a higher wage can be relied upon to lead to a decrease in the quantity of final output sold. Nor do I see any reason to think those receiving non-wage income will systematically want to purchase more labor-intensive commodities than the commodities purchased by those receiving primarily wages.

A large literature explains the analysis of the choice of technique. The above explanation of the implications of the arithmetic of cost minimization is one (non-novel) element of some recent papers, for example:

Update: Originally posted 27 April 2006. Updated 9 December 2006 to reflect movement of White URL and inclusion of drawing.

The invalid argument behind this position is shown in a simple diagram of the labor market. The x axis is the level of employment. (In other words, the x axis is the flow of labor services.) The y axis is the wage, that is, the price of labor services. We are only interested in the region where both employment and the wage are positive. The supply of labor is typically drawn as an upward-sloping line, showing more people want jobs at a higher wage. The demand for labor from firms is a downward-sloping line. The point of interestion shows the market-clearing wage (on the y axis) and the level of employment when the market clears. A law imposing a minimum wage is represented by a horizontal line above the level of the market-clearing wage. Since labor demand slopes down, this line intersects the demand curve at a level of employment less than the market-clearing level. Furthermore, the horizontal distance along this line between this point of intersection and the point of intersection of this horizontal line with the supply curve shows the level of unemployment ultimately created by the imposition of a minimum wage.

|

| Figure 1: An Incorrect Model |

Consider firms in a vertially integrated industry producing some quantity of net output. The firms know of various processes for producing commodities in each sector of the industry. Given prices, including wages, they choose the cost-minimizing technique. In a situation of capital-reversing (also known as a positive real Wicksell effect) firms adopt a technique which employs more labor per unit output at a higher wage.

Now this adoption of a more labor-intensive technique might be swamped by the effect on the level of output. But, as far as I know, nobody thinks that the income effect of a higher wage can be relied upon to lead to a decrease in the quantity of final output sold. Nor do I see any reason to think those receiving non-wage income will systematically want to purchase more labor-intensive commodities than the commodities purchased by those receiving primarily wages.

A large literature explains the analysis of the choice of technique. The above explanation of the implications of the arithmetic of cost minimization is one (non-novel) element of some recent papers, for example:

- Anthony Aspromourgos 2001. "Is Labour Cheapening a Means to Reducing Involuntary (Labour) Unemployment?" History of Economics Review, V. 34: 7-18.

- Vienneau, R. L. (2005). "On Labour Demand and Equilibria of the Firm", The Manchester School, V. 73, N. 5 (Sep): 612-619.

- Graham White 2001. "The Poverty of Conventional Economic Wisdom and the Search for Alternative Economic and Social Policies". The Drawing Board: An Australian Review of Public Affairs, V. 2, N. 2 (Nov.): 67-87.

Update: Originally posted 27 April 2006. Updated 9 December 2006 to reflect movement of White URL and inclusion of drawing.

Friday, December 08, 2006

Worldwide Distribution of Wealth

A new study, by the World Institute for Development Economics Research of the United Nations University, shows richest 2% own half of world's wealth.

Thursday, December 07, 2006

Keynesianism as the Economics of Robinson Crusoe

On the positive effect of workers' higher wages:

"If their wages were low and despicable, so would be their living; if they got little, they would spend but little, and trade would presently feel it; as their gain is more or less, the wealth and strength of the whole kingdom would rise or fall." -- Daniel DeFoe (1704). Giving Alms No Charity

Wednesday, December 06, 2006

Pasinetti On "Non-Substitution" Theorem

"...in a production context...it makes no sense to talk of 'endowments' of given physical quantities if these physical quantities, to be carried over from one period to another, are the unknowns to be determined. It makes no sense to talk of 'scarce' resources, if these resources can be produced in whatever quantities may be needed by the economic system...

When all inputs are themselves produced, a change in the composition of demand simply means that more of some inputs and less of other inputs will have to be produced, while the optimum technique remains the same. In other words, the process of adaptation to any given change in the composition of final demand is, in a production context, radically different from the one considered by traditional theory. Whereas, with given and fixed inputs (the traditional case), the only way to adapt is through a change of technique which may allow the substitution of some inputs for others, in a production context in which all inputs are themselves produced the obvious way to adapt is to produce the inputs which are needed and to cut down production of those which are no longer needed. There is no question of changing the technique. Input substitution, in a production context, has no role to play...

Another route which has been pursued to minimize the importance of the new results...consists in attributing the irrelevance of substitution to the 'very special' case of no joint production and constant coefficients [ = constant returns to scale -RLV ]. But the inconsistency of this contention is here brought into sharp relief by the very analysis of the previous pages...

As already pointed out...the joint production and nonconstant coefficients case is more complicated than, but not basically different from, the case concerning single products and constant coefficients. The complication arises from the fact that a change of the composition of demand may entail a change of the optimum technique and of the price structure. However, this does not enable us to say anything about the direction in which the input proportions will change.

...It is precisely the unambiguous direction in which relative prices and input proportions are related to each other that justifies talking of 'substitution.' But there is nothing of the sort in a production context. No general relation exists between the changes in the price structure and changes in the input proportions. More specifically, no monotonic inverse relation exists, in general, between the variation of any price, relative to another price, and the variation of the proportions among the two inputs to which these two prices refer. When this is so, to talk of 'substitution' among these inputs no longer makes any sense." -- Luigi L. Pasinetti, Lectures on the Theory of Production, Columbia University Press, 1977, pp. 186-188

Sunday, December 03, 2006

Physics And Economics - Two Quotes

"There really is nothing more pathetic than to have an economist or a retired engineer try to force analogies between the concepts of physics and the concepts of economics. How many dreary papers have I had to referee in which the author is looking for something that corresponds to entropy or to one or another form of energy." -- Paul SamuelsonI get this quote, originally from Samuelson's "Nobel" prize lecture, secondhand from Philip Mirowski, More Heat Than Light: Economics as Social Physics, Physics as Nature's Economics (Cambridge University Press, 1989). This and Mirowski's later Machine Dreams: Economics Becomes a Cyborg Science (Cambridge University Press 2002) are required reading for anybody interested in the relationship between economics and the natural sciences.

I find amusing the proposed course deletions in the following:

"The real problem with my proposal for the future of economics departments is that current economics and finance students typically do not know enough mathematics to understand (a) what econophysicists are doing, or (b) to evaluate the neo-classical model (know in the trade as 'The Citadel') critically enough to see, as Alan Kirman put it, that 'No amount of attention to the walls will prevent The Citadel from being empty'. I therefore suggest that the economists revise their curriculum and require that the following topics be taught: calculus through the advanced level, ordinary differential equations (including advanced), partial differential equations (including Green functions), classical mechanics through modern nonlinear dynamics, statistical physics, stochastic processes (including solving Smoluchowski-Fokker-Planck equations), computer programming (C, Pascal, etc.) and, for complexity, cell biology. Time for such classes can be obtained in part by eliminating micro- and macro-economics classes from the curriculum. The students will then face a much harder curriculum, and those who servive will come out ahead. So might society as a whole." -- Joseph L. McCauley and Cobera, "Response to 'Worrying Trends in Econophysics", Physica A

Wednesday, November 29, 2006

Duncan Foley's Adam's Fallacy: A Guide to Economic Theology

The authors of a number of blogs have been going on about supposed non-economists' or anti-economists' attacks on "economics". For some reason, Duncan K. Foley's latest book is held up as an example of such an attack. Since I have actually read the book under discussion, I thought I would comment.

This book is very introductory, and is not directed towards somebody like me. It's purpose is to give others something to read as an introduction to economics, something that is more recent than Robert L. Heilbroner's The Worldly Philosophers. You will not find any detailed examination here of Ricardo's texts to decide if the Sraffian surplus-based approach, the Hollander new interpretation, or some other reading is a more accurate understanding of Classical economics. Even when Foley summarizes my favorite critique of marginalism (e.g., on John Bates Clark on pp. 164-166, on time on pp. 173-174), it is so summary that I would not expect anybody with economic training to understand Foley's point.

The book is organized around discussions on great economists: A. Smith, Malthus, Ricardo, Marx, early marginalists (Jevons, Menger, John Bates Clark, Pareto), Veblen, Keynes, Hayek, and Schumpeter. (Neither Mill appears in the index.) I do not find most of Foley's discussion to be negative or an attack on these economists. Foley, in his "great books" approach, often treats these authors as putting forth the ideas that they are associated with in economics textbooks. For example, Walras is said to have invented a fictional auctioneer (p. 170). This is not an approach that finds favor with contemporary historians of ideas, who seem to prefer "thick" histories alive to shifts in discursive formations.

What about "Adam's fallacy"? Foley objects to a tendency to use general principles, supposedly independent of history, to argue for political conclusions. He wants economists to concern themselves with how things work out under the specific institutions prevailing in given times and places. That is, he wants economists to look at the world, instead of reasoning a priori. And although Foley recognizes "Adam's fallacy" in some of the economists he examines, he also recognizes it is accompanied by subtexts with an analysis more like what Foley recommends. I might have been happier with the label of the "Ricardian vice" for "Adam's fallacy".

Reminder to myself: I want to read Solow's review of Foley's book. That review appears in the 16 November 2006 issue of The New York Review of Books.

This book is very introductory, and is not directed towards somebody like me. It's purpose is to give others something to read as an introduction to economics, something that is more recent than Robert L. Heilbroner's The Worldly Philosophers. You will not find any detailed examination here of Ricardo's texts to decide if the Sraffian surplus-based approach, the Hollander new interpretation, or some other reading is a more accurate understanding of Classical economics. Even when Foley summarizes my favorite critique of marginalism (e.g., on John Bates Clark on pp. 164-166, on time on pp. 173-174), it is so summary that I would not expect anybody with economic training to understand Foley's point.

The book is organized around discussions on great economists: A. Smith, Malthus, Ricardo, Marx, early marginalists (Jevons, Menger, John Bates Clark, Pareto), Veblen, Keynes, Hayek, and Schumpeter. (Neither Mill appears in the index.) I do not find most of Foley's discussion to be negative or an attack on these economists. Foley, in his "great books" approach, often treats these authors as putting forth the ideas that they are associated with in economics textbooks. For example, Walras is said to have invented a fictional auctioneer (p. 170). This is not an approach that finds favor with contemporary historians of ideas, who seem to prefer "thick" histories alive to shifts in discursive formations.

What about "Adam's fallacy"? Foley objects to a tendency to use general principles, supposedly independent of history, to argue for political conclusions. He wants economists to concern themselves with how things work out under the specific institutions prevailing in given times and places. That is, he wants economists to look at the world, instead of reasoning a priori. And although Foley recognizes "Adam's fallacy" in some of the economists he examines, he also recognizes it is accompanied by subtexts with an analysis more like what Foley recommends. I might have been happier with the label of the "Ricardian vice" for "Adam's fallacy".

Reminder to myself: I want to read Solow's review of Foley's book. That review appears in the 16 November 2006 issue of The New York Review of Books.

Tuesday, November 28, 2006

Wittgenstein and Soviet Communism

On being recommended a couple of sources, I have been reading about Wittgenstein's political opinions, especially as in regard to Russian communism. Apparently, he was inspired by Tolstoy and thought a classless society sounded like a fine idea.

While I was looking up old articles in the New Left Review, I took a gander at the "Special Dossier" on Sraffa in the November-December 1978 issue. Sraffa and Wittgenstein seem to have this in common: the documentary evidence on their views on a whole host of interesting topics is slim.

References

While I was looking up old articles in the New Left Review, I took a gander at the "Special Dossier" on Sraffa in the November-December 1978 issue. Sraffa and Wittgenstein seem to have this in common: the documentary evidence on their views on a whole host of interesting topics is slim.

References

- Eagleton, Terry (1982). "Wittgenstein's Friends", New Left Review, N. 135 (Sep.-Oct.): 64-90

- Ferrata, Giansiro (1978). "An Argument with Gramsci in 1924", New Left Review, N. 112 (Nov.-Dec.): 67-71

- Garegnani, Pierangelo (1978). "Sraffa's Revival of Marxist Economic Theory: An Interview with Pierangelo Garegnani", New Left Review, N. 112 (Nov.-Dec.): 71-75

- Moran, John (1972). "Wittgenstein and Russia", New Left Review, N. 135 (Sep.-Oct.): 64-90

- Napoleoni, Claudi (1978). "Sraffa's 'Tabula Rasa'", New Left Review, N. 112 (Nov.-Dec.): 71-77

- Napolitano, Giorgio (1978). "Our Debt to Sraffa", New Left Review, N. 112 (Nov.-Dec.): 65-67

- Ranchetti, Fabio (1978). "Keynes, Sraffa and Capitalist Crisis", New Left Review, N. 112 (Nov.-Dec.): 78-80

- Robinson, Christopher C. (2006). "Why Wittgenstein is Not Conservative: Conventions and Critique", Theory and Event, V. 9, N. 3

- Roncaglia, Alessandro (1978). "The 'Rediscovery' of Ricardo", New Left Review, N. 112 (Nov.-Dec.): 80-82

- Sraffa, Piero (1978). "An Unpublished Letter from Piero Sraffa to Angelo Tasca", New Left Review, N. 112 (Nov.-Dec.): 82-83

Sunday, November 26, 2006

Milton Friedman’s Intellectual Integrity

I think I saw reference in some obituaries to Milton Friedman’s “intellectual integrity”. Friedman was an important intellectual figure and had many qualities. Apparently, he loved developing an argument, was unfailingly polite, and never became angry at disagreement. But, given the literature of a few short years ago, intellectual integrity is not a quality I would choose to emphasize.

Harry Johnson, in his Ely lecture at the annual meeting of the American Economic Association, considered how Friedman and his allies had promulgated the monetary counter-revolution. Johnson suggests that one might more successfully promote a counter-revolution if one is willing to misrepresent one’s opponents and encourage a lack of scholarship among one’s acolytes. That is, one should actively discourage them from checking out what proponents of other views actually say. Johnson doesn’t exactly say Friedman illegitimately bends his arguments to fit his pre-existing political biases; instead he presents his account as an application of Friedman’s “as-if” methodology:

One aspect of Friedman’s claims is his lack of originality. He claimed to not take his ideas from Keynes, but to draw on the wisdom of a prior Chicago “oral tradition”. But some think no such oral tradition existed; Friedman made it up. I forget where I read this charge – I think in a Don Patinkin essay collected in one of his books.

Friedman’s policy precepts did not work in practice, either. His ideas strongly influenced the monetary authorities on either side of the Atlantic during the Reagan and Thatcher administrations. I’d like to be able to turn to Cambridge economists here, specifically Kaldor (1982). But I only know Kaldor’s most well-developed critique of monetarism secondhand, through, for example, Turner (1993). (Kaldor was an early proponent of the “endogenous money” approach.)

Apparently, Friedman encouraged Wald in his development of sequential testing. This is an useful approach to classical statistical hypothesis testing in which the sample size is not pre-specified, but turns out to be no larger than needed. It has industrial applications in, for example, reliability acceptance testing.

References

Harry Johnson, in his Ely lecture at the annual meeting of the American Economic Association, considered how Friedman and his allies had promulgated the monetary counter-revolution. Johnson suggests that one might more successfully promote a counter-revolution if one is willing to misrepresent one’s opponents and encourage a lack of scholarship among one’s acolytes. That is, one should actively discourage them from checking out what proponents of other views actually say. Johnson doesn’t exactly say Friedman illegitimately bends his arguments to fit his pre-existing political biases; instead he presents his account as an application of Friedman’s “as-if” methodology:

”Indeed, I find it useful in posing and treating the problem to adopt the ‘as-if’ approach of positive economics, as expounded by the chief protagonist of the monetarist counter-revolution, Milton Friedman, and to ask: suppose I wished to start a counter-revolution in monetary theory, how would I go about it – and specifically, what could I learn about the technique from the revolution itself? To pose the question in this way is, of course, to fly in the face of currently accepted professional ethics, according to which purely scientific considerations and not political considerations are presumed to motivate scientific work, but I can claim the protection of the ‘as if’ methodology against any implication of a slur on individual character or a denigration of scientific work.” – Johnson(By the way, Johnson is also scathing on my favorite group of economists, the Italian-Cambridge school.)

One aspect of Friedman’s claims is his lack of originality. He claimed to not take his ideas from Keynes, but to draw on the wisdom of a prior Chicago “oral tradition”. But some think no such oral tradition existed; Friedman made it up. I forget where I read this charge – I think in a Don Patinkin essay collected in one of his books.

Friedman’s policy precepts did not work in practice, either. His ideas strongly influenced the monetary authorities on either side of the Atlantic during the Reagan and Thatcher administrations. I’d like to be able to turn to Cambridge economists here, specifically Kaldor (1982). But I only know Kaldor’s most well-developed critique of monetarism secondhand, through, for example, Turner (1993). (Kaldor was an early proponent of the “endogenous money” approach.)

Apparently, Friedman encouraged Wald in his development of sequential testing. This is an useful approach to classical statistical hypothesis testing in which the sample size is not pre-specified, but turns out to be no larger than needed. It has industrial applications in, for example, reliability acceptance testing.

References

- Johnson, Harry G. (1971). “The Keynesian Revolution and the Monetarist Counter-Revolution”, American Economic Review, V. 61, N. 2 (May): 1 -14

- Kaldor, Nicholas (1982). The Scourge of Monetarism, Oxford University Press

- Turner, Marjorie S. (1993). Nicholas Kaldor and the Real World, M. E. Sharpe

Saturday, November 25, 2006

Kurz and Salvadori on the "Non-Substitution" Theorem

“The ‘non-substitution theorem’ states that under certain specified conditions, and taking the rate of profit (rate of interest) as given from outside the system, relative prices are independent of the pattern of final demand. The ‘non-substitution theorem’ is of particular interest in the present context since, as was already mentioned, it puts into sharp relief the role of demand in neoclassical theory…

…The theorem was received with some astonishment by authors working in the neoclassical tradition since it seemed to flatly contradict the importance attached to consumer preferences for the determination of relative prices… This astonishment is all the more understandable, since several ‘classroom’ neoclassical models, for didactical reasons, are based precisely on the set of simplifying assumptions … underlying the theorem without however arriving at the conclusion that demand does not matter…

It is therefore not so much assumptions [of the production model] which account for the theorem: it is rather the hypothesis that the rate of profit (or, alternatively, the wage rate) is given and independent of the level and composition of output. This hypothesis is completely extraneous to the neoclassical approach and in fact assumes away the role played by one set of data from which that analysis commonly begins: given initial endowments…

… It goes without saying that in the framework of classical analysis with its different approach to the theory of value and distribution, a characteristic feature of which is the non-symmetric treatment of the distributive variables… there is nothing unusual or exceptional about the ‘non-substitution theorem’.” --H. D. Kurz and N. Salvadori (1995). Theory of Production: A Long-Period Analysis, Cambridge University Press: 26-28.

Tuesday, November 21, 2006

No Influence Of Tastes On Prices (Part 2 of 2)

3.0 Price System

In the first part, I present quantity flows per worker for three island economies facing the same technological possibilities. By assumption, these island economies have adpated production to requirements for use. Since the wage happens to be the same on all three islands, profit-maximizing firms have adopted the same technique of production. The prices that prevail on these islands are stationary. Assuming the wage is paid at the end of the year, the price system given by Equations 1 and 2 will be satisfied:

The wage can be found in terms of the rate of profits:

Suppose the wage, assumed identical across all three islands, is $ 3/8 per person-year. Then the rate of profits is 100%, and the price of rye is $ 2/3 per bushel. On Alpha, workers consume their wages entirely in rye. Consequently, each worker eats 9/16 bushels rye each year. On Beta, workers consume only wheat. A Beta worker eats 3/8 bushels wheat per year. Gamma is an intermediate case where workers consume three bushels rye for every bushel wheat. A Gamma worker eats 3/8 bushels rye and 1/8 bushels wheat each year.

Note that the quantity flows specified previously show the wage entirely consumed and profits entirely invested. This characteristic of the example is not necessary to the conclusion that the difference in tastes among the islanders need have no effect on prices.

4.0 Conclusion

Under the conditions satisfied by this example, different tastes have no influence on prices. If the economy is fully adapted to different tastes, the same prices can prevail.

In the first part, I present quantity flows per worker for three island economies facing the same technological possibilities. By assumption, these island economies have adpated production to requirements for use. Since the wage happens to be the same on all three islands, profit-maximizing firms have adopted the same technique of production. The prices that prevail on these islands are stationary. Assuming the wage is paid at the end of the year, the price system given by Equations 1 and 2 will be satisfied:

(1)

where p is the price of a bushel rye, w is the wage, and r is the rate of profits. I have implicitly assumed in the above equations that the price of a bushel wheat is $1.(2)

The wage can be found in terms of the rate of profits:

More work is required to express the rate of profits in terms of the wage:(3)

The price of rye, in terms of the rate of profit, is given by Equation 5:(4)

(5)

Suppose the wage, assumed identical across all three islands, is $ 3/8 per person-year. Then the rate of profits is 100%, and the price of rye is $ 2/3 per bushel. On Alpha, workers consume their wages entirely in rye. Consequently, each worker eats 9/16 bushels rye each year. On Beta, workers consume only wheat. A Beta worker eats 3/8 bushels wheat per year. Gamma is an intermediate case where workers consume three bushels rye for every bushel wheat. A Gamma worker eats 3/8 bushels rye and 1/8 bushels wheat each year.

Note that the quantity flows specified previously show the wage entirely consumed and profits entirely invested. This characteristic of the example is not necessary to the conclusion that the difference in tastes among the islanders need have no effect on prices.

4.0 Conclusion

Under the conditions satisfied by this example, different tastes have no influence on prices. If the economy is fully adapted to different tastes, the same prices can prevail.

Monday, November 20, 2006

No Influence Of Tastes On Prices (Part 1 of 2)

1.0 Introduction

This short sequence of posts illustrates the so-called non-substitution theorem. (Luigi Pasinetti argues this theorem is misleadingly named.)

Consider three islands, Alpha, Beta, and Gamma, where a competitive capitalist economy exists on each island. These islands are identical in some respects and differ in others. The point is to understand that differences in tastes need have no influence on prices.

All three islands have the same Constant-Returns-to-Scale technology available. They also face the same wage, and have fully adapted production to requirements for use. Thus, they will choose to adopt the same technique. This technique consists of a process to produce rye and another one to produce wheat. Each process requires a year to complete. Each process requires inputs of labor, rye, and wheat. These processes fully use up their inputs in producing their output. Table 1 specifies the coefficients of production for the selected technique.

2.0 Quantity Flows

The employed labor force grows at a rate of 100% per year on each island. Each island differs, however, in the mix of outputs that they produce. Table 2 shows the quantity flows per employed laborer on Alpha. Notice that the commodity inputs purchased at the start of the year total 5/32 bushesl rye and 1/16 bushels wheat. Since the rate of growth is 100%, 5/16 bushels rye and 1/8 bushels wheat will be needed for inputs into production in the following year. This leaves 9/16 bushels rye available for consumption at the end of the year per employed worker.

Table 3 shows the quantity flows on Beta. Here the same sort of calculations reveal that Beta has 3/8 bushels wheat available for consumption at the end of the year per employed worker.

Gamma's quantity flows, shown in Table 4, are an intermediate case. Gamma has 3/8 bushel rye and 1/8 bushel wheat available for consumption at the end of the year per employed worker.

In the next part, I will describe a system of prices consistent with each and every one of the three islands.

This short sequence of posts illustrates the so-called non-substitution theorem. (Luigi Pasinetti argues this theorem is misleadingly named.)

Consider three islands, Alpha, Beta, and Gamma, where a competitive capitalist economy exists on each island. These islands are identical in some respects and differ in others. The point is to understand that differences in tastes need have no influence on prices.

All three islands have the same Constant-Returns-to-Scale technology available. They also face the same wage, and have fully adapted production to requirements for use. Thus, they will choose to adopt the same technique. This technique consists of a process to produce rye and another one to produce wheat. Each process requires a year to complete. Each process requires inputs of labor, rye, and wheat. These processes fully use up their inputs in producing their output. Table 1 specifies the coefficients of production for the selected technique.

| Inputs Hired At Start Of Year | Rye Industry | Wheat Industry |

|---|---|---|

| Labor | 1 Person-Year | 1 Person-Year |

| Rye | 1/8 Bushel | 3/8 Bushel |

| Wheat | 1/16 Bushel | 1/16 Bushel |

| Outputs | 1 Bushel Rye | 1 Bushel Wheat |

The employed labor force grows at a rate of 100% per year on each island. Each island differs, however, in the mix of outputs that they produce. Table 2 shows the quantity flows per employed laborer on Alpha. Notice that the commodity inputs purchased at the start of the year total 5/32 bushesl rye and 1/16 bushels wheat. Since the rate of growth is 100%, 5/16 bushels rye and 1/8 bushels wheat will be needed for inputs into production in the following year. This leaves 9/16 bushels rye available for consumption at the end of the year per employed worker.

| Inputs | Rye Industry | Wheat Industry |

|---|---|---|

| Labor | 7/8 Person-Year | 1/8 Person-Year |

| Rye | 7/64 Bushel Rye | 3/64 Bushel Rye |

| Wheat | 7/128 Bushel Wheat | 1/128 Bushel Wheat |

| Outputs | 7/8 Bushel Rye | 1/8 Bushel Wheat |

| Inputs | Rye Industry | Wheat Industry |

|---|---|---|

| Labor | 1/2 Person-Year | 1/2 Person-Year |

| Rye | 1/16 Bushel Rye | 3/16 Bushel Rye |

| Wheat | 1/32 Bushel Wheat | 1/32 Bushel Wheat |

| Outputs | 1/2 Bushel Rye | 1/2 Bushel Wheat |

| Inputs | Rye Industry | Wheat Industry |

|---|---|---|

| Labor | 3/4 Person-Year | 1/4 Person-Year |

| Rye | 3/32 Bushel Rye | 3/32 Bushel Rye |

| Wheat | 3/64 Bushel Wheat | 1/64 Bushel Wheat |

| Outputs | 3/4 Bushel Rye | 1/4 Bushel Wheat |

Thursday, November 16, 2006

Some Correspondence

"Dear Mr. Buckley:

In your recent column praising Milton Friedman [NR, Feb. 17] you mention Adam Smith's discussion of entrepeneurs' 'animal spirits'. The full quote is: 'A large proportion of our positive actions depend on spontaneous optimism rather than on a mathematical expectation, whether moral or hedonistic or economic. Most, probably of our decisions to do something positive, the full consequences of which will be drawn out over many days to come, can only be taken as a result of animal spirits - of a spontaneous urge to action rather than inaction, and not as the outcome of a weighted average of quantitative benefits multiplied by quantitative probabilities... Only a little more than an expedition to the South Pole, is [enterprise] based on an exact calculation of benefits to come. Thus if the animal spirits are dimmed and the spontaneous optimisim falters, leaving us to depend on nothing but a mathematical expectation, enterprise will fade and die.' Unfortunately for your desire to appear as a bona-fide conservative, this is from John Maynard Keynes's General Theory, not Adam Smith's Wealth of Nations.

Some time ago Dr. Friedman reread Keynes and found more wisdom there than appears among his so-called Keynesian followers. Perhaps you would find the same." -- Robert Vienneau in "Notes & Asides", National Review (2 March 1992)

"Dear Mr. Vienneau: Drat! Because I know that Keynes quote. And the fault was not Mr. Friedman's. He said Keynes, I miswrote Smith. Thanks for reminding me of that striking passage. You are welcome to reproduce it and send it to all Democratic legislators." -- William F. Buckley, ibid

"Dear Mr. Vienneau

Bill Buckley sent on to me a copy of your letter of January 16 commenting on his use of the term 'animal spirits' in his column. You are of course right and, though Bill's column was based on a long discussion with me, I doubt very much that I was the source of his misattribution since I know full well that the term is Keynes's.

However, I write not for that reason but to express my pleasure in finding a reader out there in the wilds who recalls a comment I first published twenty years ago, and recalls it so accurately. Many thanks." -- Milton Friedman, Personal Communication (10 February 1992)

"Dear Dr. Friedman

I was deeply honored to receive your letter of February 10. Thanks for the compliments." -- Robert Vienneau, Personal Communication (25 February 1992)

Wednesday, November 15, 2006

Nobel Prize In Economics For Sraffa?

Here's somebody named Yves Gingras on the "Nobel" prize for economics. Can I say Piero Sraffa won the Nobel prize in economics?

"...on 23 March 1961, in Stockholm, the King of Sweden, Gustav-Adolph, presented [Sraffa] with the Söderstrom gold medal of the Royal Academy of Sciences. This honorary distinction, which antedated the Nobel Prize for Economics, was also awarded to John Maynard Keynes and Gunnar Myrdal." -- Jean-Pierre Potier (Piero Sraffa: Unorthodox Economist (1898-1983), Routledge, 1991)On the other hand, I don't expect the real fake Nobel to be awarded anytime soon for work in the history of economics.

Tuesday, November 14, 2006

I Dig Snow And Rain And Bright Sunshine...

...and wind, too. About 50 miles north of here, in a quite inhospitable area, an installation exists of about one hundred of these windmills. I doubt any good vantage place exists on the surface of the earth to see them all.

I wonder if this is still a defensible view:

I wonder if this is still a defensible view:

"...the direct use of solar energy has been subject to special attention and persistent hopeful claims. A very careful scholar, Denis Hayes..., claimed a few years ago that 'solar technology is here,...we can use it now.' What is here now are only several feasible recipes - useful in several special situations. But a viable technology based on solar energy is not yet here. The proof is that in spite of the substantial funds spent by the US government and many private institutions to search for a solution, no one has tried to produce a pilot plant that would use exclusively its harnessed solar energy to reproduce at least the collectors with which it was initially endowed. Solar collectors for home use have been in commerce for the past century... In spite of some failures, there have been some improvements; but the basic principle of the conversion has not progressed at all. At this time, direct solar energy is just a parasite of the current technology, as electricity and, lest we forget, gasohol are." -- Nicholas Georgescu-Roegen (1986)Environmental economists should be interested in Sraffian economics. England (1986) is a start. I suppose I should also look for something that references Schefold (1989).

- Richard W. England (1986). "Production, Distribution, and Environmental Quality: Mr. Sraffa Reinterpreted as an Ecologist", Kyklos, V. 39: 230-244

- Nicholas Georgescu-Roegen (1986). "Man and Production," in Foundations of Economics: Structures of Inquiry and Economic Theory, (edited by Mauro Baranzini and Roberto Scazzieri), Basil Blackwell

- Bertram Schefold (1989). Mr. Sraffa on Joint Production and Other Essays, Unwin-Hyman

Saturday, November 11, 2006

What We Learn When We Learn About Economics

Christopher Hayes sat in on the University of Chicago's introductory economics class. He recounts his experiences in "What We Learn When We Learn About Economics", an article in the November issue of In These Times, a progressive or soft-left American publication.

One can quibble with aspects of Hayes articles. The Chicago school is only a subset of neoclassical economics, not all of neoclassical economics. (Compare and contrast the role of the "Chicago boys" in Chile and the "Harvard boys" in Russia. Does Hayes' error matter?) I'm not at all sure Hayes understands "efficiency" as "Pareto efficiency". (But wouldn't that be Allen Sanderson's fault?) In general, Allen Sanderson comes off as an ignoramus, I think. Does he really suggest to the kids that who gets what is a matter of who is willing to "work hard"? Whatever happened to Hayek's understanding of abstract rules and entrepreneurship? I doubt Sanderson has ever read Gunnar Myrdal's The Political Element in the Development of Economic Theory. As I understand it, whatever the label, Steve Forbes is not an advocate of a flat tax; he doesn’t want to tax property income.

(Hat tip toMark Thoma and Ezra Klein.)

Update: Hayes' article is the subject of a post with many comments at Crooked Timber.

One can quibble with aspects of Hayes articles. The Chicago school is only a subset of neoclassical economics, not all of neoclassical economics. (Compare and contrast the role of the "Chicago boys" in Chile and the "Harvard boys" in Russia. Does Hayes' error matter?) I'm not at all sure Hayes understands "efficiency" as "Pareto efficiency". (But wouldn't that be Allen Sanderson's fault?) In general, Allen Sanderson comes off as an ignoramus, I think. Does he really suggest to the kids that who gets what is a matter of who is willing to "work hard"? Whatever happened to Hayek's understanding of abstract rules and entrepreneurship? I doubt Sanderson has ever read Gunnar Myrdal's The Political Element in the Development of Economic Theory. As I understand it, whatever the label, Steve Forbes is not an advocate of a flat tax; he doesn’t want to tax property income.

(Hat tip toMark Thoma and Ezra Klein.)

Update: Hayes' article is the subject of a post with many comments at Crooked Timber.

Friday, November 10, 2006

A. Smith Explains Source Of Profits In Exploitation Of The Worker

Karl Marx described the source of profits, interest, and rent as value added by workers not paid out in wages. That is, Marx said the value of a commodity produced under capitalism is the sum of the value of the goods worked up by the workers into that commodity and the value added by workers. Insofar as this value-added is not fully paid out to the workers, they are exploited. But, according to Marx, capitalism is sustainable only when a source exists for returns to capital, that is, only when workers are exploited. Adam Smith said much the same:

Update: Gavin Kennedy agrees with me that Smith thought the (embodied) labor theory of value inapplicable to commercial society, in which laborers do not obtain all of their produce. For some reason, Kennedy presents his agreement as disagreement. (Although I did not go into it in my original post, I also hold that Smith did not have a labor commanded theory of value, as opposed to a labor commanded theory of welfare.)

Selected References

"As soon as stock has accumulated in the hands of particular persons, some of them will naturally employ it in setting to work industrious people, whom they will supply with materials and subsistence, in order to make a profit by the sale of their work, or by what their labour adds to the value of the materials... The value which the workmen add to the materials, therefore, resolves itself in this case into two parts, of which one pays their wages, the other the profits of their employer upon the whole stock of materials and wages which he advanced." -- Adam Smith (1976, Book I, Chapter VI)Smith provided the same explanation of profit a few chapters later, albeit mixed with an account of the source of rent:

"The produce of labour constitutes the natural recompence or wages of labour.This reading of Adam Smith, in which he offers an account of the source of profits in the exploitation of workers, was a commonplace in the 19th century among the so-called Ricardian socialists. I find it of interest that Adam Smith offers this account while rejecting the (embodied) labor theory of value. I'm not sure this account makes sense, as a quantitative approach, without the labor theory of value, or, at least, without Marx's invariants (see Table 8). I do not think the tremendous continuity, as well as differences, between the ideas of Adam Smith and of Karl Marx is any secret among scholars.

In that original state of things, which precedes both the appropriation of land and the accumulation of stock, the whole produce of labour belong to the labourer. He has neither landlord nor master to share with him...

...As soon as land becomes private property, the landlord demands a share of almost all the produce which the labourer can either raise, or collect from it. His rent makes the first deduction from the produce of the labour which is employed upon land.

It seldom happens that the person who tills the ground has wherewithal to maintain himself till he reaps the harvest. His maintenance is generally advanced to him from the stock of a master, the farmer who employs him, and who would have no interest to employ him, unless he was to share in the produce of his labour, or unless his stock was to be replaced to him with a profit. This profit makes a second deduction from the produce of the labour which is employed upon land.

The produce of almost all other labour is liable to the like deduction of profit. In all arts and manufactures the greater part of the workmen stand in need of a master to advance them the materials of their work, and their wages and maintenance till it be completed. He shares in the produce of their labour, or in the value which it adds to the materials upon which it is bestowed; and in this share consists his profit." -- Adam Smith (1976, Book I, Chapter VIII)

Update: Gavin Kennedy agrees with me that Smith thought the (embodied) labor theory of value inapplicable to commercial society, in which laborers do not obtain all of their produce. For some reason, Kennedy presents his agreement as disagreement. (Although I did not go into it in my original post, I also hold that Smith did not have a labor commanded theory of value, as opposed to a labor commanded theory of welfare.)

Selected References

- Smith, Adam (1776). An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations

- Thompson, Noel W. (1984). The People's Science: The Popular Political Economy of Exploitation and Crisis 1816-34, Cambridge University Press

Thursday, November 09, 2006

Marx And Commentators On Marx On The Justice Of Capitalism (Part 3 Of 3)

In part 1, I quoted Marx arguing against criticizing capitalism on the basis that it is unfair. In part 2, I showed some current scholars are well aware of this reading of Marx. Here I look back at Engels and the golden age of the Second International.

Lenin, of course, had a world-wide impact on history. He wrote a lot, but the pamphlet from which the following quotation is taken is one of his more well-known works:

"In the Critique of the Gotha Programme, Marx goes into some detail to disprove the Lassallean idea of the workers' receiving under Socialism the 'undiminished' or 'full product of their labour.' Marx shows that out of the whole of the social labour of society, it is necessary to deduct a reserve fund, a fund for the expansion of production, for the replacement of worn-out machinery, and so on; then, also, out of the means of consumption must be deducted a fund for the expenses of management, for schools, hospitals, homes for the aged, and so on..." -- V. I. Lenin (1932), Chapter V., Sect. 3I stumbled upon a book by Boudin in some used bookstore. I don't know much about him. I think he was an American. Here we see that even a less celebrated commentator on Marx gets my point in this series of posts:

"In his great work on capital and interest, where more than one hundred pages are devoted to the criticism of this theory, Böhm-Bawerk starts out his examination of the theory by characterizing it as the 'theory of exploitation' and the whole trend of his argument is directed towards one objective point: to prove that the supposedly main thesis of this theory, that the income of the capitalists is the result of exploitation, is untrue; that in reality the workingman is getting all that is due to him under the present system. And the whole of his argument is colored by his conception of the discussion as a controversy relative to the ethical merits or demerits of the capitalist system... We therefore advisedly stated in the last chapter that in employing the adjectives 'necessary' and 'surplus' in connection with labor or value, it is not intended to convey any meaning of praise or justification in the case of the one, nor of condemnation or derogation in the case of the other. As a matter of fact, Marx repeatedly stated that the capitalist was paying to the workingman all that was due him when he paid him the fair market value of his labor power. In describing the process of capitalist production, Marx used the words, 'necessary' and 'surplus' in characterizing the amounts of labor which are necessarily employed in reproducing what society already possesses and that employed in producing new commodities or values. He intended to merely state the facts as he saw them, and not to hold a brief for anybody." -- Louis Boudin (1907).Engels had a lot to do with how Marx is interpreted and understood. Some question whether some of Engels' interpretations were misleading and too oversimplified. But here I think Engels is correct in his overall point about what Marx wrote: