4.0 PricesThe argument proceeds by determining which technique is cost minimizing when the firms in all industries are in equilibrium. In this context, a full industry equilibrium has the following properties:

- At least one corn-producing process is operated, and at least one steel-producing process is operated

- The cost of inputs, including interest charges, for each process in operation does not exceed revenues

- No process can be used to obtain pure economic profits

I assume that steel and corn inputs are paid for at the beginning of the year. Labor, although hired at the beginning of the year, is paid out of the product at the end of the year.

(Notice the above conditions are not enough to specify a general equilibrium. Utility maximization, the supply of originary factors, and the demand for consumption goods, for example, are not modeled.)

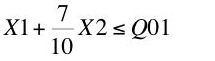

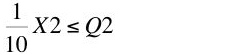

Given the above conditions, Equations 1 and 2 must be satisfied if the Alpha technique is adopted by the firms:

(1)

(1)

(2)

(2)

where corn is the numeraire,

p is the price of steel,

w1 is the wage of category 1 labor,

w2 is the wage of category 2 labor, and

r is the rate of profits (sometimes called the interest rate). The constants in Equation 1 come from the steel-producing process (Process A) in the alpha technique. The constants in Equation 2 come from the corn-producing process (Process D). Equations 1 and 2 provide a system of two equations in four unknowns. Thus, two degrees of freedom exist in this system. The system can be solved for the wage of category 1 labor and the price of steel in terms of a given rate of profits and a given wage of category 2 labor.

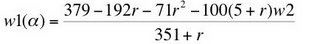

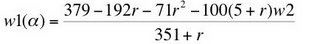

(3)

(3)

(4)

(4)

Equation 3 is the so-called factor price surface for the Alpha technique. This is a two-dimensional surface in a three-dimensional space.

Corresponding solutions for the systems of equations arising for the Beta, Gamma, and Delta techniques are relegated to Appendix C.

5.0 Choice of TechniqueThe system of equations described in Section 4 for a given technique guarantee that costs, including interest charges, do not exceed revenues for the processes comprising that technique. They also guarantee that no pure economic profits can be earned by operating either one of those processes. They do not guarantee that no pure economic profits can be earned in the processes outside that technique. That is, it remains to be shown which technique is cost-minimizing. The so-called factor-price frontier can be used to analyze the choice of technique.

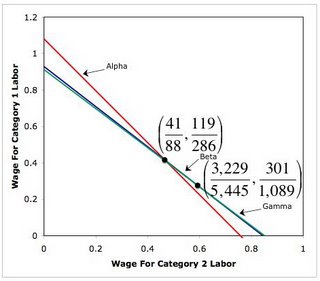

For this example, the factor-price frontier is a two-dimensional surface in a three-dimensional space. The dimensions of that space are the rate of profits and the wages for the two categories of labor. I consider a slice through the frontier for two separate values of the rates of profits.

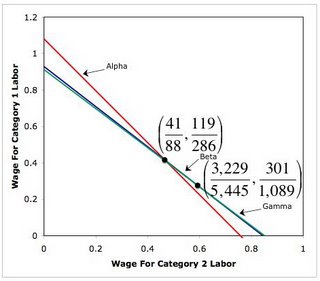

5.1 A Rate of Profits of 0%Figure 2 shows the factor-price curves for three techniques when the rate of profits is zero. (The curve for the Delta technique is never on the frontier formed from the outer envelope of these curves, and it is not shown.) The cost-minimizing technique at a given rate of profits and a given wage of category 2 labor maximizes the wage of category 1 labor. Thus, for a rate of profits of zero percent, the Alpha technique is cost minimizing at a low wage of category 2 labor, the Beta technique is cost-minimizing at an intermediate wage, and the Gamma technique is cost-minimizing at a high wage. (Notice that the curves for the techniques are straight lines in the figure. This is a general implication of the mathematics. Reswitching of techniques cannot arise at a given level of the rate of profits for varying levels of the wages of the two categories of labor.)

|

| Figure 2: Factor Price Fronter At r = 0% |

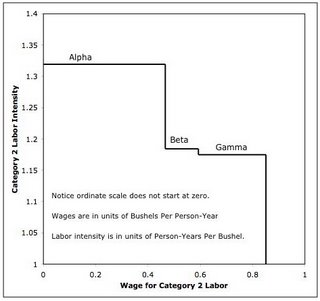

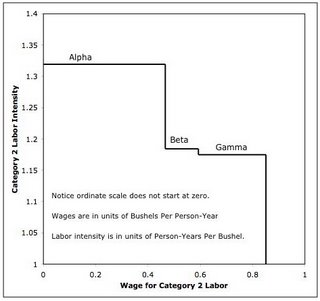

Since the technique and prices have been determined at a zero percent rate of profits, for any given wage of category 2 labor, one can graph the labor intensity for category 2 labor for the cost-minimizing technique against the wage of category 2 labor. Figure 3 shows the result. In this case, a higher wage of category 2 labor is associated with a step-decrease in the labor intensity of category 2 labor. For this specific example, the behavior at an interest rate of zero percent seems to conform to ill-educated and outdated neoclassical intuition about factor substitution.

|

| Figure 3: Category 2 Labor Intensity Versus Wage At r = 0% |

5.2 A Rate of Profits of 150%Figure 4 shows the factor-price curves on the frontier when the rate of profits is 150 percent. In this case, the Gamma technique is cost-minimizing at a low wage of category 2 labor, while the Beta technique is cost-minimizing at a high wage.

|

| Figure 4: Factor Price Fronter At r = 150% |

Figure 5 shows the labor-intensity of category 2 labor graphed against the wage of category 2 labor. In this case, a higher wage is associated with a choice of technique in which a

more labor intensive technique. It is mathematically incorrect to state that, given typical neoclassical assumptions, firms will substitute another category of labor if the wage of one category of labor is increased.

|

| Figure 5: Category 2 Labor Intensity Versus Wage At r = 150% |

6.0 ConclusionSo much for explaining wages and employment by the interaction of well-behaved supply and demand functions for labor categories in any practical application, as such functions are understood in neoclassical economics.

(A counterargument would show how to draw empirically-applicable, downward-sloping labor demand functions in this and related examples; point out some typical neoclassical assumption violated in this and related examples; state empirically validated special-case conditions on, say, technology that rule out these sort of Sraffa effects; show how the rejection of the old-fashioned neoclassical story about substitution effects is consistent with typical applications; or, perhaps, reject such applications.)

Appendix CAppendix C.1 Beta Prices (C-1)

(C-1)

(C-2)

(C-2)

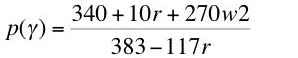

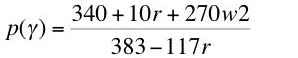

Appendix C.2 Gamma Prices (C-3)

(C-3)

(C-4)

(C-4)

Appendix C.3 Delta Prices (C-5)

(C-5)

(C-6)

(C-6)

References- Kurz, Heinz D. and Neri Salvadori (1995). Theory of Production: A Long-Period Analysis, Cambridge University Press

- Metcalfe, J. S. and Ian Steedman (1972). "Reswitching and Primary Input Use", Economic Journal